Earlier this year I only spent a week in Myanmar, by flying in to Mandalay and going to Bagan. The travel timeline was short but I wanted to be sure I could go to Myanmar and at least see it. I didn’t know anything about Myanmar except the Rohingya genocide, but I knew that I wouldn’t be going to Rakhine state, that I wouldn’t be learning much more about current politics. This was a short-term tourist gig. I wasn’t expecting to be drawn to the music.

A bus journey was necessary to get from Mandalay to Bagan - a 6 hour bus journey covering only about 120 miles! But it was on the bus when I heard this melodic, hauntingly beautiful pop music. This song still haunts me because I never learned the title of the song, and I can’t pinpoint it through youtube. So I will have to wait for the day when I’m listening through all this music and stumble upon it. Or, when I go back to Myanmar and ask everyone, desperately, for the title of this song.

Since the 1930s Burmese artists were recording music that resembled the Western style from British rule. But over time the pop music scene that had thrived was banned by the nationalist government in the 1960s and 1970s that sought to eliminate all foreign threats to Burmese “traditions.” Burmese artists were sometimes recruited to write propaganda for the totalitarian Burma Socialist Program Party, which ruled the country from 1962 until the 8888 uprising in 1988. Artists had to submit their songs for government review and censorship, and were unable to write commentary about poverty, human rights, and democracy.

But with new technology, artists subverted the main channels, producing their own tapes that came to be known as “stereo” (because the government-sponsored music was recorded in mono). Sai Htee Saing became a household name along with his band “The Wild Ones,” paving the way for ethnic Shan artists.

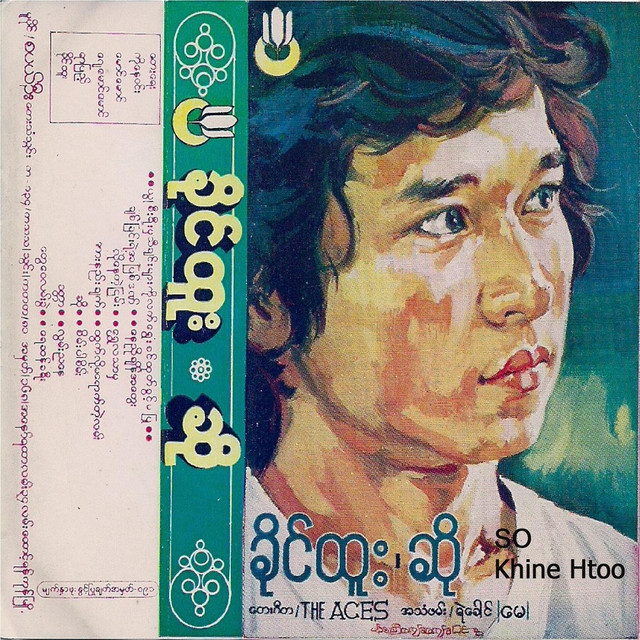

Khine Htoo

This song by Khine Htoo even sounds a bit like “Sweet Home Alabama.” A song by Min Min Latt is another example of stereo. I especially appreciate the ebb and flow of in-tune, out of tune; and the similarity it bears to Korean rock.

Admittedly a lot of the music I’ve listened to sounds like it would be great for karaoke night (pink flashing subtitles can be found at the bottom of the videos) but I don’t think this is necessarily a bad thing. There are sweet melodies, songs that to my ear, sound like they’re about romance and longing, and they tend to hover around the same tempo - slow and easy. For example, songs by May Sweet and Khine Htoo. But so much of Myanmar’s popular music scene sounds the same - often using the same few notes - so I understand why critics say there should be more innovation and diversity.

“After decades of military rule, Burmese music continues to struggle with forces that seem to conspire to prevent its development, both artistically and as a form of social expression.”

It’s difficult to see how Myanmar’s music can really grow and develop, like much of the country, if the government does not want its people to flourish. At least until 2004, words including “‘mother’, ‘dark’, ‘truth’, ‘blood’ and ‘rose’ are prohibited” from songs. And, “officials have banned any songs about courageous women” (Zaw, p51). But I can’t really know about all of this unless I gain the necessary language skills.

Currently, as around the world, hip-hop, rap, and punk are popular among young people and are pathways to dream about a brighter future. But this is still only among mainstream, likely more educated and wealthy Myanmarese communities; which, probably face the same strict censorship as in the years before. “‘Young people are now seeking an outlet for their frustrations. They need to be persuaded to channel their potential for betterment. We as singers have a responsibility,’ says Zaw Win Htut.” (Zaw, p60) More about Myanmar’s singers in exile here.

Myanmar’s got my attention mainly because of its diverse, complicated history, and continuing struggles. I’m not exactly sure why it’s more special to me than any other place, but there’s something about being there and being really confused about the social and political dynamics, and now coming home trying to learn more about it, and still being baffled by the disconnect between widespread, longstanding atrocities side by side an idealized version of traveling there (don’t have to look too far on youtube or instagram to find this narrative). Something about that absolute ignorance, and my own ignorance, of the language, music, history, and culture really humbles and inspires me.

Sources used and additional reading:

Aung Zaw. 2004. Ch. 6, “Burma: Music Under Seige.” In Shoot the Singer!: Music Censorship Today.

Levin, Dan. 2014. “Searching for Burmese Jade, and Finding Misery.” New York Times.

Mahtani, Shibani. 2014. “Meet the New Rich In… Myanmar.” The Wall Street Journal.

Rieffel, Lex. 2018. “Myanmar Economy Grows Despite Refugee Crisis.” Brookings Institute.

Zin, Min. 2002. “Burmese Pop Music: Identity in Transition.” The Irrawaddy.